It is easy to be a ‘free trader’ while your economy is dominant. It is a lot more difficult to hold the line when your economic dominance is being eroded. I am referring of course to the blog titled “Low cost of labor – How long will it last?” published by Monique Rupert, who is a good friend and colleague, in which she refers to an article by Dan Gilmour of Supply Chain Digest titled “Rethinking China.” It is tough to disagree with a friend and colleague, but I feel I must, but perhaps more so with the original article by Dan Gilmour. In his introduction Dan apologizes for being political in his column. I must too, though I would hope that both of us are more in search of solutions than being political. It is less the factual evidence Dan provides to which I disagree than the sentiment. For decades the US has railed against closed economies and through its dominance of the World Bank has enforced (I use the term loosely) its version of market economics on countries without the social and political structures to absorb the huge economic shocks and resultant social consequences on countries that had to come begging to the World Bank. No, I am not a socialist. In fact I am a lot closer to a believer in market economics. But there are times when a less purist interpretation of market economics can lead to less human suffering. I know, I know: Market economists will argue that slow change is only postponed pain. Perhaps. But isn’t it market economics that Monique and Dan are arguing against? The relentless rise and rise and rise of China as an economic power driven by the need to find ever cheaper sources of supply for the western economies? I am a British citizen, so I am well acquainted with the slow and steady decline of power and influence. While my 15 year old daughter would be surprised to hear that I did not live during the Victorian era, which was the height of British power and influence, I have experienced the dramatic shift in the manufacturing power of the UK over the past 50 years. It is not an easy thing to live through and accept. As late as the 1950’s the UK was the second largest car manufacturer in the world and the largest exporter of cars. One has only to look at the figures for the last 10 years to see the continued decline to the point that there isn’t a single UK based mass production brand left and the number of vehicles produced dropped 22 percent between 2000 and 2010. You can just imagine what the combination of declining volumes and increased efficiencies have done to the employment figures.

Source: http://www.smmt.co.uk/reports-publications/industry-data/

And yet there can be no question that the general standard of living in the UK has increased tremendously over the past 50 years, largely driven by the financial sectors and entertainment, but also by the general growth of the world wide economy. There is no doubt that many individuals have suffered tremendously over the past 50 years as the manufacturing base dwindled to almost nothing. According to the World Bank the UK economy as a whole grew, very well in fact. In comparing the economies I used the value of “GDP per capita (current USD)” which the World Bank defines as:

GDP per capita is gross domestic product divided by midyear population. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. It is calculated without making deductions for depreciation of fabricated assets or for depletion and degradation of natural resources. Data are in current U.S. dollars.

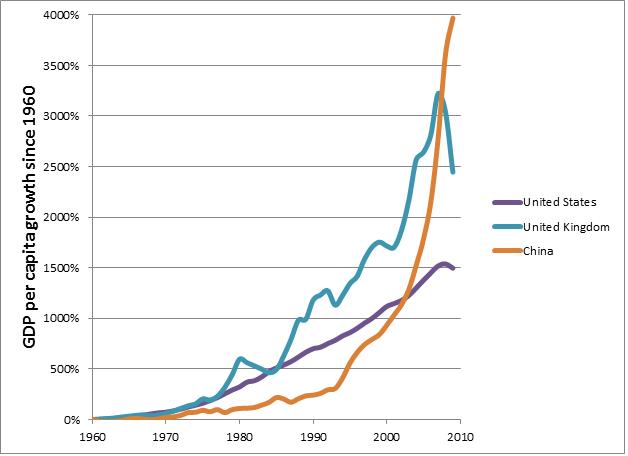

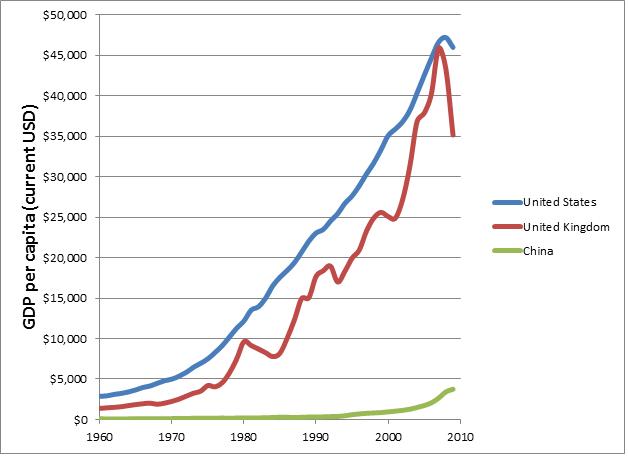

When we compare the US, the UK, and China over the past decades we can see that the UK experienced greater GDP per capita growth than the US, but China has lagged quite far behind until as little as 10 years ago. The GDP per capita growth is measured from the base of 1960, not the year-on-year growth because I wanted to illustrate the overall increase of the quality of life (using GDP per capita as a proxy) in the UK while the manufacturing sector has shrunk considerably during this period. The second graph illustrates that the GDP per capita in China is still only about 10 percent of the GDP per capita in the US, despite the huge gains over the last 10 years.

http://data.worldbank.org/country

In other words, the emergence of China as a world economic power does not represent a zero-sum conundrum for the US and other western economies. The average Joe in the street may still see an increase in standard of living while the relative economic and political power of the US is diminished. One only has to read “Guns, Germs, and Steel” by Jared Diamond to understand the inevitable ebb and flow of power over the millennia to understand that absolute pre-eminence is difficult to maintain. It simply costs too much to maintain a country’s preeminence. According to Wikipedia it won a Pulitzer Prize and the Aventis Prize for Best Science Book in 1998, so there are plenty of people in the US who thought very highly of the book. There is also an excellent short discussion of the book on the PBS web site. There is a great article in the December 2, 2010 edition of The Economist titled “The dangers of a rising China” which probably requires a subscription to read on the internet. After discussing some of the threats posed by China, the authors go on to state that:

Pessimists believe China and America are condemned to be rivals. The countries’ visions of the good society are very different. And, as China’s power grows, so will its determination to get its way and to do things in the world. America, by contrast, will inevitably balk at surrendering its pre-eminence. They are probably right about Chinese ambitions. Yet China need not be an enemy. Unlike the Soviet Union, it is no longer in the business of exporting its ideology. Unlike the 19th-century European powers, it is not looking to amass new colonies. And China and America have a lot in common. Both benefit from globalisation and from open markets where they buy raw materials and sell their exports. Both want a broadly stable world in which nuclear weapons do not spread and rogue states, like Iran and North Korea, have little scope to cause mayhem. Both would lose incalculably from war.

Let us hope that “cooler heads” prevail on both sides of the US-China divide. Quite honestly I believe it is a matter of giving a little to get a lot, not only for the US and China, but for all western economies as well as the other BRIC countries. But let us get back to more prosaic discussions of supply chain management. Yes, as Monique and Dan point out, it is at the heart of the manufacturing and economic power shift we are seeing. This is because an efficient supply chain makes it economically viable to use labor half way around the world and still bring the product to market more cheaply than before. Of course cheap labor costs make a huge difference, but if efficient supply chains did not exist this would not matter. Either the cost would be too high, eroding the advantage of a lower cost of labor, or the product would arrive in the market too late to capture changing trends in consumer buying patterns. But let us not forget that the rise of the British Empire was as much to do with the development of rail and the power of the British merchant marine fleet as it did with the Industrial Revolution. There is no doubt that the Industrial Revolution had an enormous impact on the efficiency with which raw materials were converted into finished products, but this would not have amounted to much if raw materials couldn’t be brought to the factories from around the world quickly and efficiently and finished products couldn’t be shipped to markets around the world quickly and efficiently. Of course by today’s standards the supply chains of the mid-1800’s were incredibly slow and inefficient, but at the time they provided huge leaps in productivity. However, the UK wasn’t just a consumer market, it also controlled the means of production and the innovation that arose from that. As Dan and Monique point out, this isn’t the case for most western economies today, perhaps with the exception of Germany. Only time will tell if this will lead to absolute decline rather than relative decline. I know I am hoping and praying for relative decline.

Leave a Reply