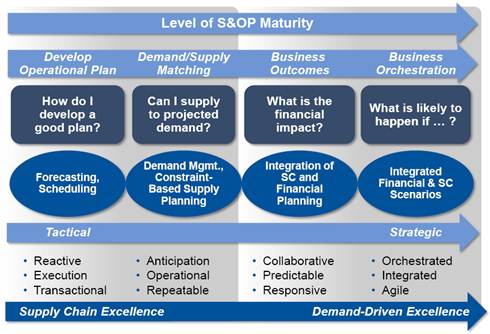

The title came to me after downloading the presentation slides from a Gartner webcast (Delivering Business Value from S&OP, Applebaum, T., Kohler, J., 29 March 2012). This is a very good presentation that outlines the reasons why most companies have not progressed beyond stage 2 of the four stage S&OP maturity model, and how best practice companies are achieving greater process maturity. Of course this is a play on the title of John Milton's epic poem, "Paradise Lost". But unlike Adam and Eve I feel as if we have not yet eaten from the "Tree of Knowledge" and it is this that is preventing us from progressing to higher levels of process maturity. We need to come to the realization that the "paradise" of the perfect plan is unattainable, which has so often been promised over the past 30 year, since the birth of Supply Chain Management. But while we continue to pursue the perfect plan by function, we will not attain the end-to-end process capabilities required to reach stage 4 of the Gartner maturity model. The four stages of maturity are described below.

In truth, the maturity model has great applicability to planning in general, not just to supply chain, and S&OP in particular. There are a number of terms used to describe the higher levels of maturity that jump off the page at me: Collaborative, Responsive, Agile. And the great framing of the primary focus of stage 4: “What is likely to happen if …” This captures so much that I think is important in good supply chain capabilities. Planning in general, not just S&OP, should be driven by this question which is both predictive – likely to happen – and exploratory – "what-if". But included in the same webcast (Delivering Business Value from S&OP, Applebaum, T., Kohler, J., 29 March 2012) was the following slide. When I first saw this slide I thought it was a really good way of capturing many of the themes central to S&OP: visibility, alignment with corporate goals, and setting operational goals.

There is one little term with which I disagree strongly that is embedded in the 4th bullet: “… when things go wrong”. Inherent in this statement is a paradigm which really needs to change. This is my paradigm lost. I’ll explain below. Implicit in the “Orchestration” stage is “demand translation”, which, in a Gartner report (Demand Management Elevates Value Network Performance, Lord, P., Steutermann, S., Salley, S. 30 March 2012) is defined as

Demand translation converts independent channel demand to dependent-demand plans and supply requirements. It is a critical capability that connects demand management to supply execution. Within the framework of DDVN, demand translation is an orchestrating response assessment capability, rather than demand management. Demand translation includes tactical decisions that select which supply network nodes should be loaded with customer demand and the operational explosion of customer demand into sourcing, production and delivery schedules, based on materials resource planning (MRP), distribution resource planning (DRP) and ATP algorithms.

But it is the market conditions, best described in a Gartner report (Agility Is More Than a Supply Chain Design Strategy, Lord, P., Barger R., Carter, K, 11 November 2011) that drive the business need for demand translation which are at the heart of my paradigm lost.

- The top three considerations for designing the supply chain response to demand were responsiveness, sustainability and lowest cost. The priorities varied by industry sector, however. The need for agility, although cited less often, is implied in the need to balance speed and cost.

- Each industry sector is struggling to balance competing design priorities, such as asset efficiency and responsiveness in process manufacturing. High tech is balancing the most complex set of considerations, with high performance gaps in efficiency, cost and collaboration.

- The two most effective approaches for designing the supply response are rapid detection and translation of demand changes, and structuring supply agreements for flexibility across a wide range of demand levels.

But yet again the last bullet describes my paradigm lost in the use of the term “demand changes”. Why is this important?

So what is my paradigm lost? It is the inherent assumption that we can forecast customer demand correctly. Demand didn’t change. What happened is that we came to realize that we had predicted demand incorrectly. Let me repeat: Demand didn’t change. This is the same assumption of paradigm that is captured in the statement “… when things go wrong”. Of course things do go wrong. Tsunamis happen, suppliers go bust, deliveries fail inspection. We make our living by helping companies deal with this type of disruption. And yes, customers change their mind after placing an order. But in my experience, born out by several studies on forecast accuracy, the greatest contributor to “demand changes” is that we didn’t predict demand correctly in the first place. What changed was not demand, but our understanding of true demand. As I have written before, the assumption that we can predict demand accurately is fatefully flawed. Well, maybe I shouldn’t be so categorical, but in the low volume/high mix industries in which I mostly work, demand volatility is such that forecast error, as measured by MAPE, is seldom below 35% for mature products and seldom below 65% for new products. Let me repeat: Demand didn’t change! We just predicted it incorrectly. Did you get my message yet? The point of my earlier blog is that even if we could forecast 100% accurately, demand variability would still exist, and it is this demand variability that drives cost into the supply chain through inventory or capacity buffers. Which is where demand translation comes into play. If the demand forecast is not that accurate, then by definition the supply plan developed to satisfy the demand cannot be more accurate, unless through a ridiculously fortuitous circumstance. I am all for placing inventory buffers at strategic locations to buffer against demand variability, but the amount of inventory required to buffer against 35%-65% forecast accuracy is enormous. Which is where postponement strategies come to play, but postponement strategies require capacity buffers. Postponement also requires a key capability identified in demand translation, namely “the operational explosion of customer demand into sourcing, production and delivery schedules, based on materials resource planning (MRP), distribution resource planning (DRP) and ATP algorithms.” But to evaluate trade-offs requires what-if analysis and the incorporation of financial metrics so that the profitability of the response can be determined. And to reach compromise and consensus based upon trade-offs requires a collaborative solution in which multiple people can make changes to the same "what-if" scenario. And if you can’t perform the "what-if" analysis quickly you might as well not do it at all. Know sooner. Act faster.

Leave a Reply