I am fascinated by the changes happening in the pharmaceutical industry and spent the latter part of last week in San Diego at the 6th Biomanufacturing Summit getting some deep exposure to a sector that is growing very quickly. Very briefly and simplistically, traditionally medicines are largely broad spectrum and small molecules, meaning they treat a lot of symptoms/causes and that they are based upon chemical compounds. These drugs have been at the heart of the pharmaceutical industry as we know it. Biologics have been around for some time, in fact ever since vaccines have been around, dating back to the late 1700s and made famous by Louis Pasteur. But they have not been at the core of the development of the pharmaceutical industry until fairly recently with Amgen’s formation in 1980. Since then many startups, such as Genetech and Genzyme, have entered the market and been gobbled up by the big boys such as Roche and Sanofi respectively. Other indications of the maturing of the industry are the passing of Amgen’s founder, George Rathman, in 2012, and the arrival of biosimilars, the generic version of biologics. The manufacturing of the modern biologics is fascinating, and is often based upon the culture of cells in Chinese hamster ovaries. As you can imagine the science is amazing and the process is difficult to manage in terms of sterilization and yield. As a consequence a lot of the Biomanufacturing Summit was focused on the interface between Development – the people who focus on the science - and Tech Ops – the people who focus on the manufacturing. Supply Chain – the people who match demand and supply - is something of an afterthought, but growing in importance.

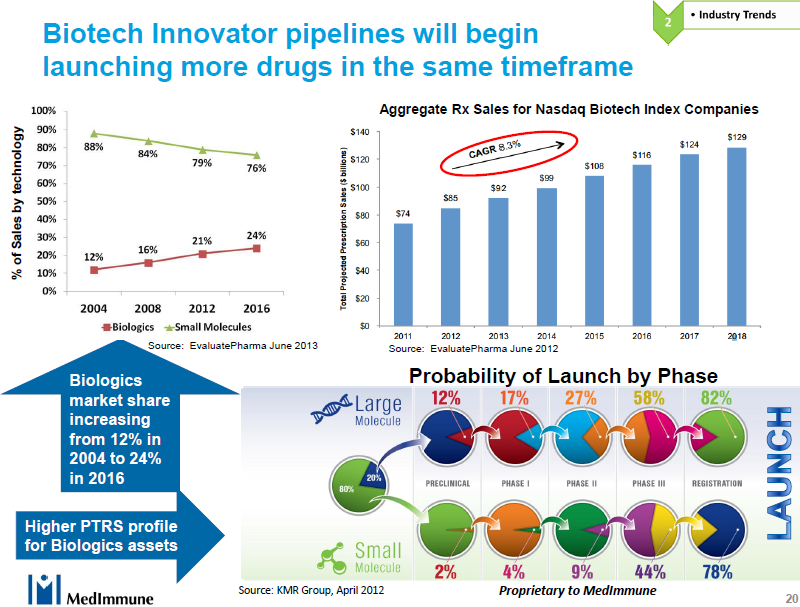

On the tech ops side there was a fascinating talk by Andy Skibo of MedImmune titled “Decision Making for Optimal Capacity Management” which focused on the difficulty of making long term capacity decision given all the uncertainties of drug efficacy and market demand. Despite the uncertainties, the biologics are still out performing small molecule drugs with the market share of biologics jumping to 24% by 2016. Perhaps more interesting, given the huge cost associated with drug development, is that biologics are more likely to be approved, by a lot. Let us look at the data in the bottom right of the diagram below from the perspective of how many drugs need to be at different stages of approval in order to have 1 drug approved.

|

Molecule |

Launch |

Registration |

Phase III |

Phase II |

Phase 1 |

Preclinical |

|

Large |

1 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

3.7 |

6.6 |

8.8 |

|

Small |

1 |

1.2 |

2.0 |

11.1 |

26.6 |

43.6 |

While early stage discovery typically costs less than late stage trials, and, as far as I know, early stage discovery for large molecules is more expensive than for small molecules, nevertheless there is a huge advantage in having a large molecule portfolio, even in the development stages. If we add revenue growth to discovery cost analysis we can see why the large cap small molecule companies are falling over themselves to buy small/medium cap companies with a strong biologic pipeline and portfolio.

But it isn’t just in drug discovery, manufacturing, and sales where the biologics are having a big impact on the industry. In every case I know of the larger small molecule parent company has adopted the supply chain practices of the biologics subsidiary. There have been some misfires and some modifications of the supply chain approaches but by and large the practices of the biologic companies have prevailed. The difference in approach can be simplified down to a much greater emphasis on the total landed cost of the network rather than just the cost of manufacturing. Nothing brings this out better than the use of COGM – cost of goods manufactured – rather than COGS – cost of goods sold – as a way of measuring operational effectiveness. Nothing captures this focus better than the title of the conference – Biomanufacturing Summit.

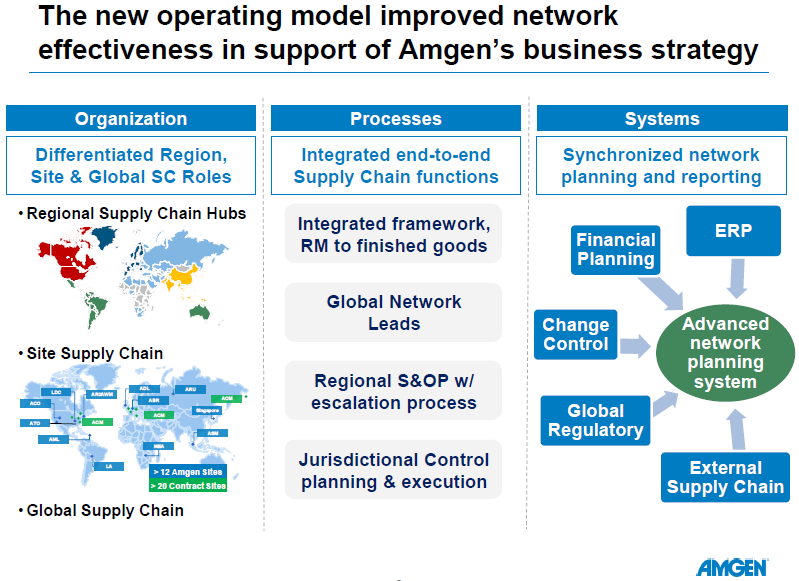

An example of this changed approach was given by Amgen who were struggling with a manufacturing centric approach as they expanded rapidly into new markets and expanded their product portfolio. (In the spirit of open disclosure I need to point out that Amgen is a Kinaxis customer.) A manufacturing centric approach could not deal with the network complexity. Amgen responded to this challenge by putting in place a supply chain organization than has a broad span of control that includes Plan, Source, and Deliver, but not Make.

A recurring theme in the conference was how much the pharmaceutical industry in general can learn from best practices in other industries, particularly High-Tech and CPG. While the overall financials of a pharmaceutical company are structured quite differently than High-tech and CPG, I am looking forward to the time when pharmaceutical companies measure their manufacturing facilities on plan conformance rather than absorption or OEE, which is fairly typical in leading companies in other industries. This would be much more consistent with the ‘every patient every time’ mantra of the pharmaceutical industry and leads naturally to a total landed cost of COGS analysis of the overall supply chain.

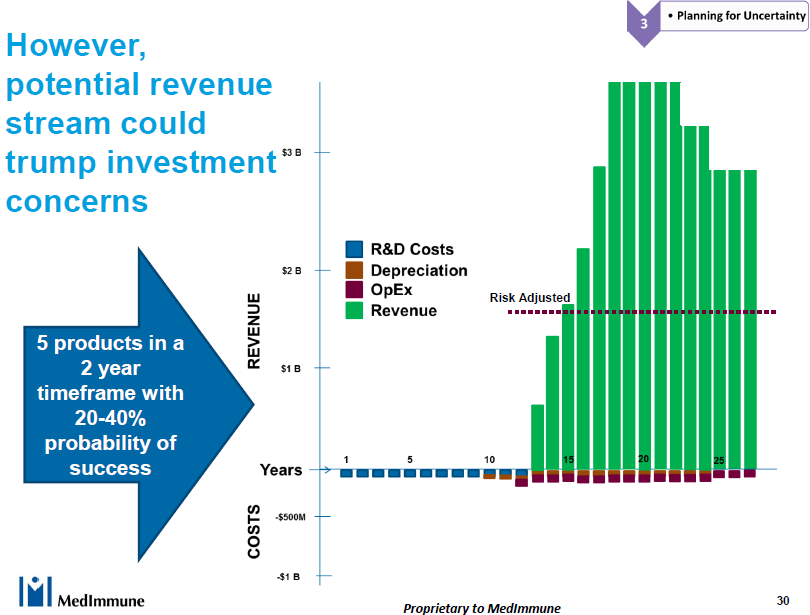

Nothing captured the shortcomings of a manufacturing centric approach better than Andy Skibo’s slide below.

Of course these are illustrative numbers, but they are directionally correct. As Andy said during his presentation, referring to the capex cost of building a new manufacturing facility,

“The [capex] costs are dust compared to the revenue.”

While it is true that the supply chain costs are also ‘dust’ when compared with the revenue, the pharmaceutical industry needs to turn that argument around and focus on patient drug availability instead. A network approach that focuses on the end-to-end supply chain is how they will reduce drug shortages, which is a chronic problem at the moment.

Leave a Reply