OK, seat backs, tray tables up, and seat belts buckled, we’re continuing a conversation reflecting on the “10 Principles of Good Design” as applied to supply chain and supply chain management (Design for the Supply Chain) and this week’s principle delves into the beauty of the supply chain design.

Principle #3: Good design “Is Aesthetic”, states:

“The aesthetic quality of a product is integral to its usefulness because products are used every day and have an effect on people and their well-being. Only well-executed objects can be beautiful.” – ‘Dieter Rams: ten principles for good design’

I kept going back and forth on if this was going to be an easy or hard topic since it was about being ‘beautiful’, but as always, all things work together for good. I was just on a flight and the Steve Jobs movie was on. Without being a fanboy, I would venture to say that Apple makes some ‘well-executed’ products that are ‘used every day and have an effect on people’. In the movie there’s a scene where Jobs goes on about the beauty of what they were making.

I came across a quote from him that further exemplifies his thinking: “When you’re a carpenter making a beautiful chest of drawers, you’re not going to use a piece of plywood on the back, even though it faces the wall and nobody will see it. You’ll know it’s there, so you’re going to use a beautiful piece of wood on the back. For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.”

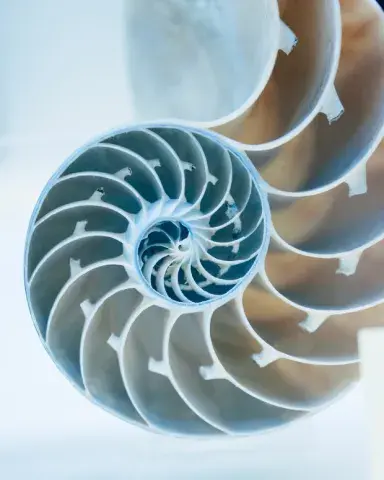

So for me this means the aesthetic in our supply chains come from the focus we put on achieving a level of excellence throughout, using “Systems Thinking” while maintaining a human-centered design. It means not cutting corners. It means being thorough and having long-term vision.

In the context of global supply chains and off-shoring, a white paper by The University of Tennessee’s Global Supply Chain Institute (GSCI) states: “In general, when organizations pursue cost-cutting without giving much thought to associated impacts on customer service, they operate in a cost world, and not a total cost of ownership or TCO world. (By TCO, we mean “full cost accounting,” where all conceivable costs both direct, indirect, and even the cost of lead-time and lost sales, are considered.)

The adoption of a short-term, cost-cutting mindset inevitably drives firms toward less than optimal decisions and strategies that will lead to poor long-term outcomes. … only a very small percentage of organizations fully consider many of the hard-to-compute supply chain costs that can severely hurt an organization’s competitive advantage. These costs include the cost of lead time, the cost of (in)flexibility, the cost of quality, the cost of lost sales, and of course the costs associated with the added risks that exist within a global environment.” Global Supply Chains - A Report by the Supply Chain Management Faculty at the University of Tennessee

When they say “cost-cutting without giving much thought to associated impacts on customer service”, that directly ties to the example of ‘using a piece of plywood in the back’. Thankfully there are a lot of traditional examples of focusing on cost cutting, production efficiency, and quality improvement that positively impact customer service and workers’ well-being, like carts made with easy access to reduce excessive reaching; arranging tools and components so that things are picked up ergonomically; dashboards to help users focus on top priority items; etc.

What excites me is the push many companies are making to be more holistic in relentlessly executing with excellence while formally incorporating environmental and community impact in their supply chain design. An example from a couple of years ago is Levi Strauss & Company and its Dockers Wellthread, “a process that pushes the envelope on sustainable design. It’s meant to connect the dots between smart design, environmental practices and the well-being of the apparel workers who make the garments.” (Levi's Wellthread stitches design together with worker well-being).

In terms of Industry 4.0, there are some obvious opportunities in capturing cradle-to-grave data to better understand the total cost of ownership beyond the enterprise and using that to drive improvements. I’m wondering if personal tools like Fitbit will be incorporated into supply chain operations to give measurable feedback on worker well-being. Will there eventually be a way to know how much stress or fun (as well as cost) went into getting me the product I just purchased so that I can say, “that was a beautiful thing”?

What’s beautiful about your supply chain?

P.S. I want to leave you with a story this design principle reminded me of. I think I heard it on a podcast, but I can’t be sure of who it’s attributed to. Long story short, a builder is retiring. His boss asks him to work on just one more house before he hangs it up and he agrees. As he’s working on this last house, he cuts corners and does sloppy work relative to the excellence he’s been known for his entire career. Once the job is completed his boss asks him to come by for a final inspection. When he arrives, his boss tells him he doesn’t need to do an inspection because he knows the work is going to be exceptional as usual. He just wanted to get him to the house to give him the keys. He was giving this employee the house to thank him for his excellent service for so many years. The story goes on to talk about the guy’s feelings, living in a house that he knew where every flaw was, etc. I just share this because we’re capable of excellence and ‘beauty’ in the supply chains we design. Let’s not grow weary in well doing! Let your aesthetics shine!

Leave a Reply